Week 5

Segmented

Assimilation Theory

SOCI 231

Lecture I: September 30th

A Quick Reminder

Response Memo Deadline

Your third response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM today.

A Quick Reminder

An Election Is Looming Over the Horizon

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Midterm Paper Deadline

Your midterm papers are due by 8:00 PM on Friday, October 25th.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

More information will be provided on Wednesday.

This Week’s Focus —

Segmented Assimilation Theory

A Reminder

Straight-Line Assimilation (Stylized)

A Reminder

Neo-Assimilation Theory (Stylized)

Another Contender

Segmented Assimilation Theory (Stylized)

Another Contender

Segmented Assimilation Theory (Stylized)

A Question

Another question about interpretation.Why do Groups A, B and C follow different trajectories?

Segmented Assimilation Theory—

Alejandro Portes, Min Zhou

and Rubén G. Rumbaut

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

Growing up in an immigrant family has always been difficult, as individuals are torn by conflicting social and cultural demands while they face the challenge of entry into an unfamiliar and frequently hostile world. And yet the difficulties are not always the same. The process of growing up American oscillates between smooth acceptance and traumatic confrontation depending on the characteristics that immigrants and their children bring along and the social context that receives them.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 75, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

When Portes and Zhou (1993) published their seminal article, scholars of “the new immigration” almost exclusively

studied the first generation.

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

This was, for a variety of reasons,

a major shortcoming.

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

Note: Data comes from the Migration Policy Institute.

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

The great deal of research and theorizing on post-1965 immigration offers only tentative guidance on the prospects and paths of adaptation of the second generation because the outlook of this group can be very different from that of their immigrant parents. For example, it is generally accepted among immigration theorists that entry-level menial jobs are performed without hesitation by newly arrived immigrants but are commonly shunned by their U.S.-reared offspring.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 76, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

Nor does the existing literature on second-generation adaptation, based as it is on the experience of descendants of pre-World War I immigrants, offer much guidance for the understanding of contemporary events … Conditions at the time were quite different from those confronting settled immigrant groups today.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 76, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

Two major differences are worth highlighting—

Race

The Structure of Economic Opportunities

Segmented Assimilation and its Variants

New Americans at a Glance

Regional Origin of Immigrants to the U.S.

Data from the Pew Research Center

Assimilation as a Problem

Disparate Assimilatory Possibilities

An emerging paradox in the study of today’s second generation is the peculiar forms that assimilation has adopted for its members … [A]dopting the outlooks and cultural ways of the native-born does not represent, as in the past, the first step toward social and economic mobility but may lead to the exact opposite. At the other end, immigrant youths who remain firmly ensconced in their respective ethnic communities may, by virtue of this fact, have a better chance for educational and economic mobility through use of the material and social capital that their communities make available.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 82, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Assimilatory Possibilities

A Question

What exactly are Portes and Zhou (1993) positing?Disparate Assimilatory Possibilities

This situation stands the cultural blueprint for advancement of immigrant groups in American society on its head. As presented in innumerable academic and journalistic writings, the expectation is that the foreign-born and their offspring will first acculturate and then seek entry and acceptance among the native-born as a prerequisite for their social and economic advancement. This portrayal … stands contradicted today by a growing number of empirical experiences.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 82, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Assimilatory Possibilities

A closer look at these experiences indicates, however, that the expected consequences of assimilation have not entirely reversed signs, but that the process has become segmented. In other words, the question is into what sector of American society a particular immigrant group assimilates.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 82, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Assimilatory Possibilities

“Instead of a relatively uniform mainstream whose mores and prejudices dictate a common path of integration, we observe today several distinct forms of adaptation.”

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 82, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Assimilatory Possibilities

Three major pathways are available—

Growing Acculturation and Parallel Integration

Downward Assimilation

Pluralist or Preservationist Adaptation

Vulnerability and Resources

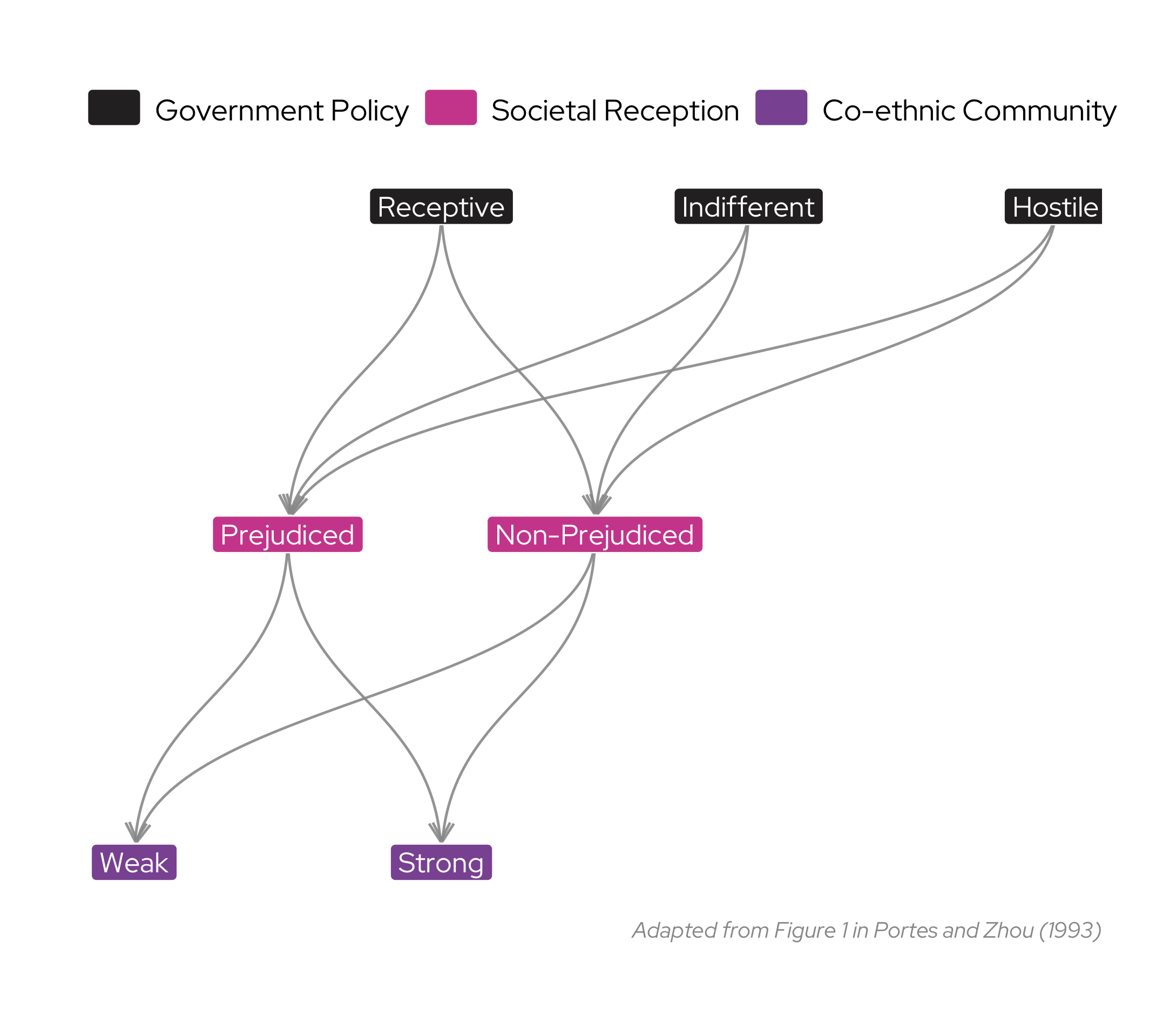

Modes of Incorporation

Along with individual and family variables, the context that immigrants find upon arrival in their new country plays a decisive role in the course that their offspring’s lives will follow. This context includes such broad variables as political relations between sending and receiving countries and the state of the economy in the latter and such specific ones as the size and structure of preexisting coethnic communities.

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 83, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Modes of Incorporation

“[M]odes of incorporation consist of the complex formed by the policies of the host government; the values and prejudices of the receiving society; and the characteristics of the coethnic community.”

(Portes and Zhou 1993, 83, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Modes of Incorporation

Three Contextual Sources of Vulnerability

Race or Skin Colour

Geospatial Proximity to Underclass

Shocks to the Host Economy

Modes of Incorporation

Three Contextual Resources

Governmental Support

Relative Insulation From Prejudice

Networks in the Coethnic Community

Modes of Incorporation

Another Detour

Back to the Oppositional Culture Thesis

Researchers have tried to determine whether the culture-behavior-outcome links postulated in the oppositional culture account can be verified using large-scale, population-level data … This work not only generally fails to verify the empirical linkage between declarative culture and on-the-ground outcomes laid out by oppositional culture theorists …. but it has instead uncovered a paradox: black youth seem to have equal or even higher commitments to pro-school goals, and they seem to make a stronger connection between success in school and status attainment in adulthood than do white students. In addition, no consistent evidence can be found that high-performing black students face a “burden of acting white” by being ostracized, teased, or dismissed by their same-race peers.

(Lizardo 2017, 102, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion I

Three Examples

In groups of 2-3, discuss how the three examples sketched by Portes and Zhou (1993)—Mexican Americans, Punjabi Americans and Haitian Americans—help illustrate the theoretical

logic behind segmented assimilation theory.

Lecture II: October 2nd

The Midterm Paper

A rubric will be uploaded by tomorrow morning.

Review

A Question

According to Portes and Zhou (1993), what are the three assimilatory pathways available to the children of immigrants?Review

From Alejandro Portes Himself

Legacies —

The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation

Not Everyone Is Chosen

The story of how a foreign minority comes to terms with its new social surroundings and is eventually absorbed into the mainstream of the host society is the cloth from which numerous sociological and economic theories have been fashioned … For the most part, this story has been told in optimistic tones and with an emphasis on the eventual integration of the newcomers … In reality, the process is neither as simple nor as inevitable.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 44–45, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Not Everyone Is Chosen

Why?

Heterogeneity Among Immigrant-Origin People

Heterogeneity in the Mainstream

Not Everyone Is Chosen

There are groups among today’s second generation that are slated for a smooth transition into the mainstream and for whom ethnicity will soon be a matter of personal choice … There are others for whom their ethnicity will be a source of strength and who will muscle their way up, socially and economically, on the basis of their own communities’ networks and resources. There are still others whose ethnicity will be neither a matter of choice nor a source of progress but a mark of subordination. These children are at risk of joining the masses of the dispossessed, compounding the spectacle of inequality and despair in America’s inner cities.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 45, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Not Everyone Is Chosen

Once again, there are three major pathways available—

Growing Acculturation and Parallel Integration

Pluralist or Preservationist Adaptation

Downward Assimilation

Not Everyone Is Chosen

[W]hile assimilation may still represent the master concept in the study of today’s immigrants, the process is subject to too many contingencies and affected by too many variables to render the image of a relatively uniform and straightforward path credible. Instead, the present second generation is better defined as undergoing a process of segmented assimilation where outcomes vary across immigrant minorities and where rapid integration and acceptance into the American mainstream represent just one possible alternative.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 45, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Not Everyone Is Chosen

Once again … why?

History of the Immigrant First Generation

Pace of Acculturation for Parents and Children

Barriers Encountered by the Second Generation

Family and Community Resources

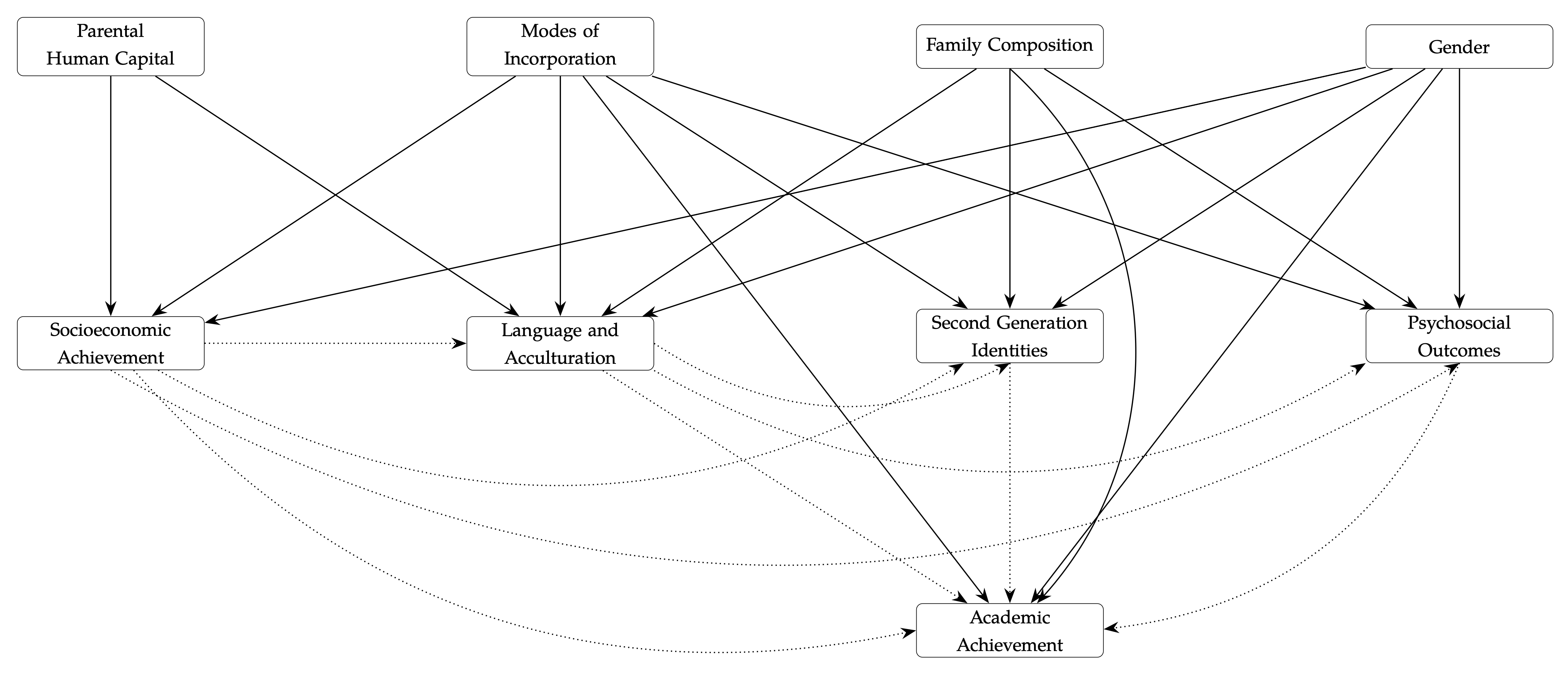

Modes of Incorporation and Their Consequences

Variation Among Immigrants

Immigrant-origin people differ along three key dimensions—

Individual-Level Attributes (e.g., age, education)

Contexts of Reception (e.g., government policies)

Family Structure (e.g., family size, parental dynamics)

Variation Among Immigrants

Adapted from Table 3.1 in Portes and Rumbaut (2001).

Note: This data is from 1990.

Group Discussion II

Three Key Dimensions

In groups of 2-3, discuss how individual-level attributes, contexts of reception, and family structure jointly—and unevenly—shape assimilatory outcomes.

Acculturation and the

Reversal of Roles

Types of Acculturation

One of the most poignant aspects of immigrants’ adaptation to a new society is that children can become, in a very real sense, their parents’ parents. This role reversal occurs when children’s acculturation has moved so far ahead of their parents’ that key family decisions become dependent on the children’s knowledge. Because they speak the language and know the culture better, second-generation youths are often able to define the situation for themselves, prematurely freeing themselves from parental control.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 52–53, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Types of Acculturation

Role reversal was a familiar event among offspring of working-class European immigrants at the beginning of the twentieth century … Today, second-generation Latins and Asians are repeating the story but with an important twist … [T]he social and economic context that allowed their European predecessors to move up and out of their families exists no more. In its place, a number of novel barriers to successful adaptation have emerged, making role reversal a warning sign of possible downward assimilation.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 53, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Types of Acculturation

Role reversal, like modes of incorporation, is not a uniform process. Instead, systematic differences exist among immigrant families and communities. It is possible to think of these differences as a continuum ranging from situations where parental authority is preserved to those where it is thoroughly undermined by generational gaps in acculturation.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 53, EMPHASIS ADDED)

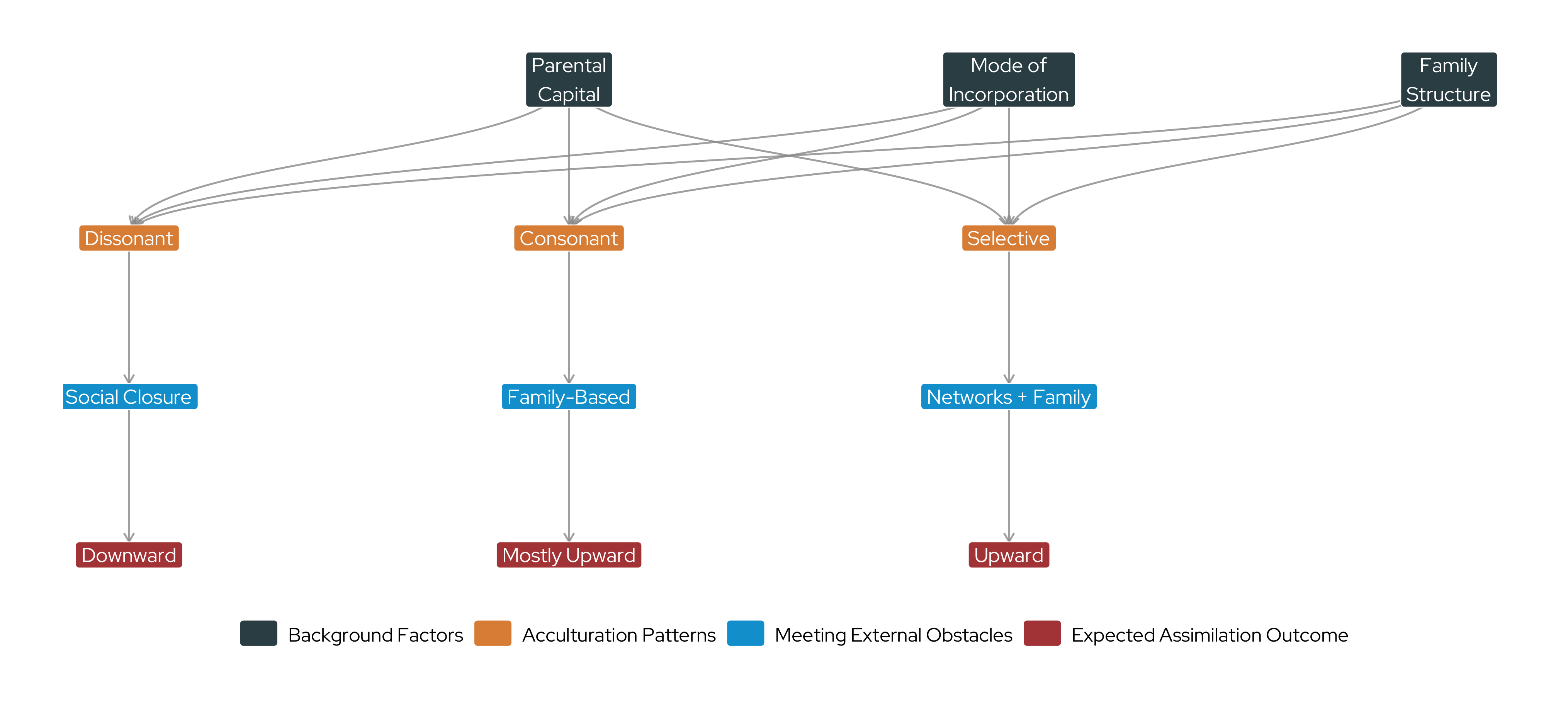

Types of Acculturation

Dissonant Acculturation

Dissonant acculturation takes place when children’s learning of the English language and American ways and simultaneous loss of the immigrant culture outstrip their parents’. This is the situation leading to role reversal, especially when parents lack other means to maneuver in the host society without help from their children.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 53–54, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Types of Acculturation

Consonant Acculturation

Consonant acculturation is the opposite situation, where the learning process and gradual abandonment of the home language and culture occur at roughly the same pace across generations. This situation is most common when immigrant parents possess enough human capital to accompany the cultural evolution of their children and monitor it.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 54, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Types of Acculturation

Selective Acculturation

[S]elective acculturation takes place when the learning process of both generations is embedded in a co-ethnic community of sufficient size and institutional diversity to slow down the cultural shift and promote partial retention of the parents’ home language and norms. This third option is associated with a relative lack of intergenerational conflict, the presence of many co-ethnics among children’s friends, and the achievement of full bilingualism in the second generation.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 54, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Types of Acculturation

| Children | Parents | Type | Expected Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Language and Customs | Embedded in Ethnic Community | American Language and Customs | Embedded in Ethnic Community | ||

| + | - | + | - | Consonant Acculturation | Joint search for integration into American mainstream; rapid shift to English monolingualism among children |

| - | + | - | + | Consonant Resistance To Acculturation | Isolation within the ethnic community; likely to return to home country |

| + | - | - | + | Dissonant Acculturation (I) | Rupture of family ties and children’s abandonment of ethnic community; limited bilingualism or English monolingualism among children |

| + | - | - | - | Dissonant Acculturation (II) | Loss of parental authority and of parental languages; role reversal and intergenerational conflict |

| + | + | + | + | Selective Acculturation | Preservation of parental authority; little or no intergenerational conflict; fluent bilingualism among children |

Disparate Outcomes

Adaption of Figure 3.1 in Portes and Rumbaut (2001).

Challenges and Resources

Reminder—Three Sources of Vulnerability

Race or Skin Colour

Geospatial Proximity to Underclass

Shocks to the Host Economy

Reminder—Three Resources

Governmental Support

Relative Insulation From Prejudice

Networks in the Coethnic Community

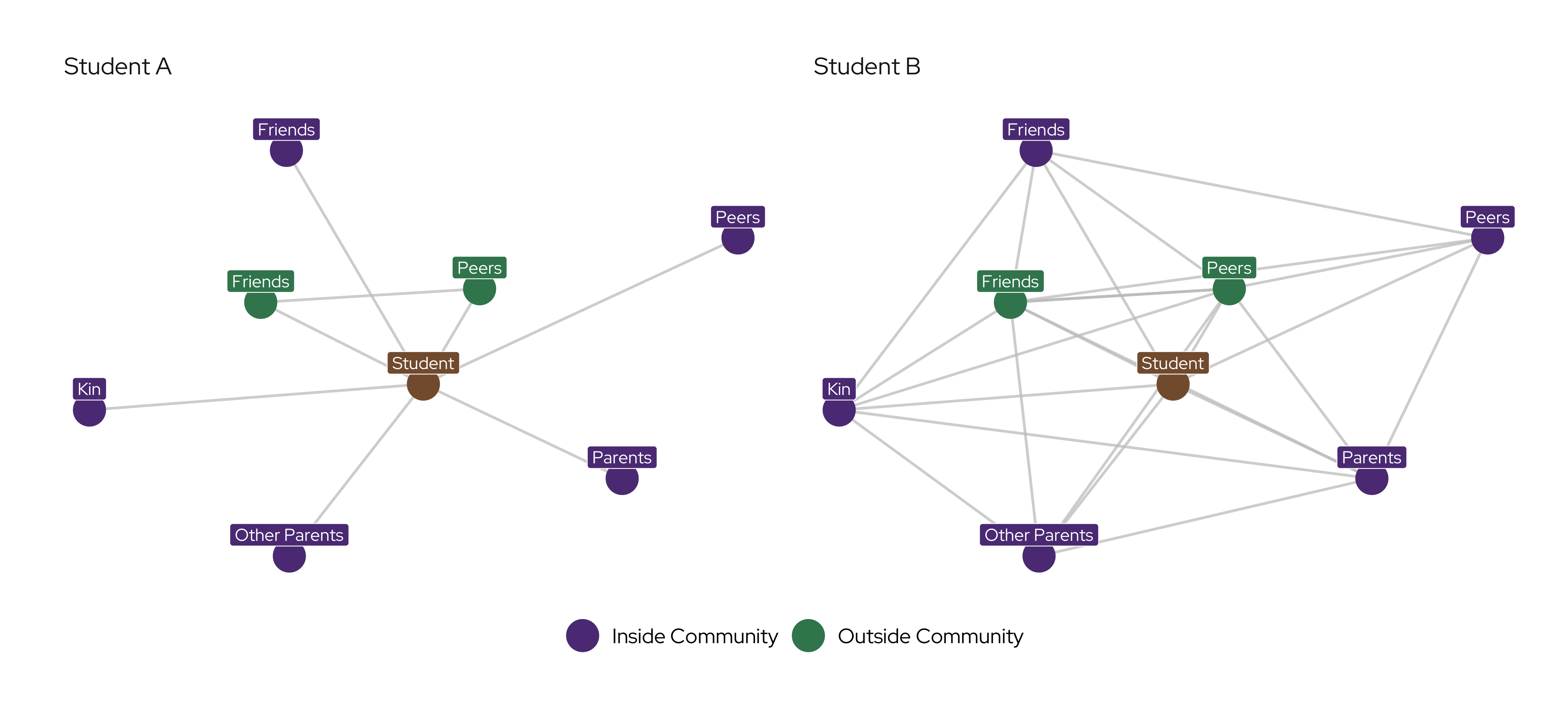

The Immigrant Co-Ethnic Community

Social capital, grounded on ethnic networks, provides a key resource in confronting obstacles to successful adaptation. First, it increases economic opportunities for immigrant parents, giving them a better chance to put to use whatever skills they brought from their home country and sometimes providing additional entrepreneurial training. Second, strong ethnic communities commonly enforce norms against divorce and marital disruption, thus helping preserve intact families. Third, the same networks directly reinforce parental authority. Social capital depends less on the relative economic or occupational success of immigrants than on the density of ties among them.

(Portes and Rumbaut 2001, 64–65, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Immigrant Co-Ethnic Community

Adaption of Figure 3.2 in Portes and Rumbaut (2001).

The Broader—and Confusing—Story

A confusing adaption of Figure 3.3 in Portes and Rumbaut (2001).

Group Discussion III

Interpreting This Stylized Summary

Group Discussion IV

A Battle of Perspectives?

In groups of 2-3, discuss whether you see segmented assimilation theory and the neo-assimilation paradigm as competing or complementary perspectives.

See You Monday

References